What are cosmic ray nuclei?

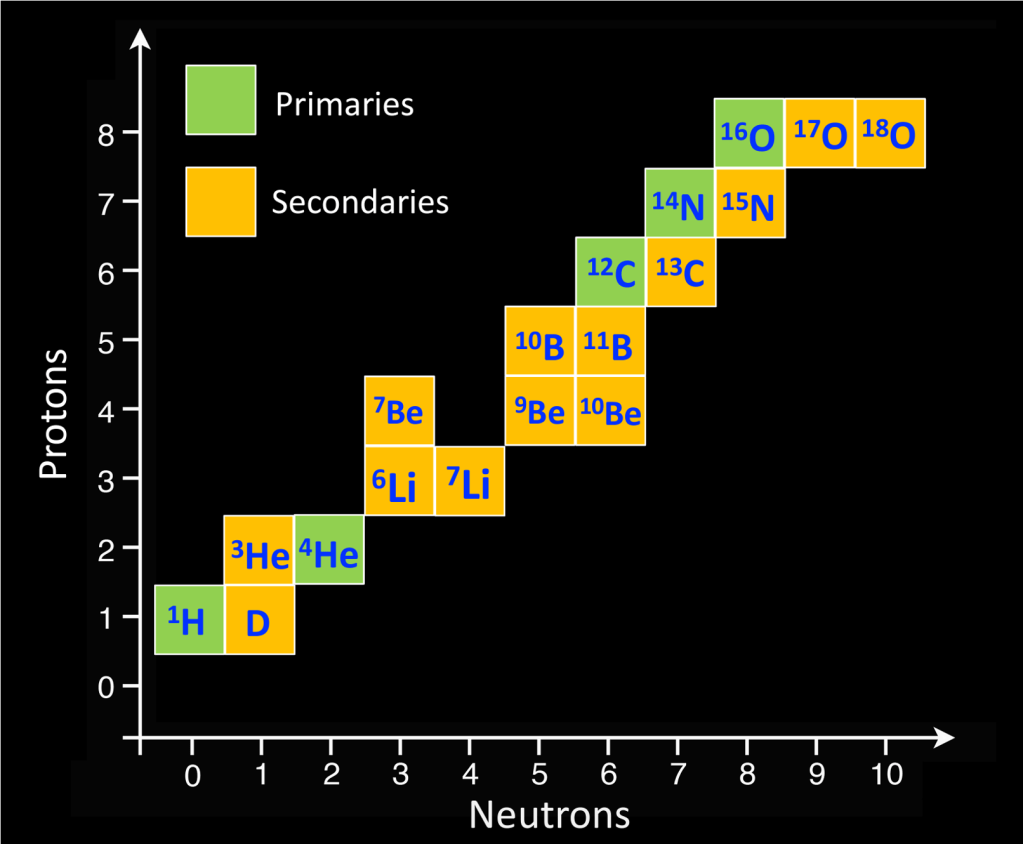

Cosmic ray nuclei — the cores of atoms — that travel through space at nearly the speed of light. They consist mainly of protons (hydrogen nuclei) and heavier nuclei such as helium, carbon, oxygen, and iron, all stripped of their electrons. These nuclei are accelerated by energetic astrophysical sources like supernova remnants and propagate through the Galaxy before reaching Earth. Studying cosmic ray nuclei helps us understand the origin, acceleration, and propagation of matter in our Galaxy.

And what are isotopes?

Atoms of the same element always have the same number of protons, but they can differ in the number of neutrons — these variants are called isotopes. For example, lithium has two stable isotopes: lithium-6 (with 3 protons and 3 neutrons) and lithium-7 (3 protons and 4 neutrons). Measuring the relative abundance of these isotopes can tell us a lot about how elements are produced and how cosmic rays propagate through the Galaxy.

Precision Measurement of Lithium Isotopes by AMS

The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS) aboard the International Space Station has just published a landmark result: the first high-precision measurement of lithium isotope fluxes in cosmic ray nuclei. The research appears in Physical Review Letters. Related press releases highlight the significance:

Using over 12 years of data and the combined power of AMS’s silicon tracker, time-of-flight detectors, and its Ring Imaging Čerenkov system, the collaboration precisely separated lithium-6 and lithium-7 isotopes in cosmic ray nuclei.

Why This Matters

Lithium nuclei in cosmic rays are secondary particles, formed by the fragmentation of heavier nuclei (like carbon and oxygen) colliding with interstellar gas. Measuring the ratio of lithium-7 to lithium-6 allows scientists to better understand these fragmentation processes and the propagation of cosmic rays through the Galaxy.

These precise isotope measurements are essential to refine models of cosmic-ray transport and to improve our understanding of elemental production in the Galaxy. They also contribute to ongoing investigations of the “cosmological lithium problem” : Big Bang Nucleosynthesis predicts 3–4 times more Li-7 than what we actually observe in old, pristine stars. AMS ruled out a significant primordial or exotic source of Li-7 in cosmic rays by showing that the Li-6/Li-7 ratio is constant and matches expectations from secondary production alone. This means all observed cosmic-ray lithium likely comes from spallation, not from primordial nucleosynthesis or other non-standard sources.

What’s Next: Beryllium and Boron Isotopes

At AMS, the MIT group — including myself — continues analyzing cosmic ray isotopes. Upcoming results on beryllium and boron are particularly exciting. The ⁽¹⁰⁾Be/⁽⁹⁾Be ratio is a powerful cosmic clock: since ¹⁰Be is radioactive with a half-life of 1.4 million years, its abundance relative to stable ⁹Be can reveal how long cosmic ray nuclei have traveled and thus probe the size of the Galactic halo.

Stay tuned for more discoveries as we continue to unravel the high-energy history of our Galaxy.